A Plot Structure

Structure is one of the most discussed and important words in fiction writing. There are many theories of what exactly structure is. Screenwriting texts and experts, for example, often declare that structure is the proper placement of plot points or the use of sequences and acts. These organizing principles are essential to a script, but they relate, I believe, not to structure but to form. Form is the external shape of a script, of how its content– its events and scenes–are molded. Form is not the content of a story. Actual structure, I believe, is the content. And content is always king.

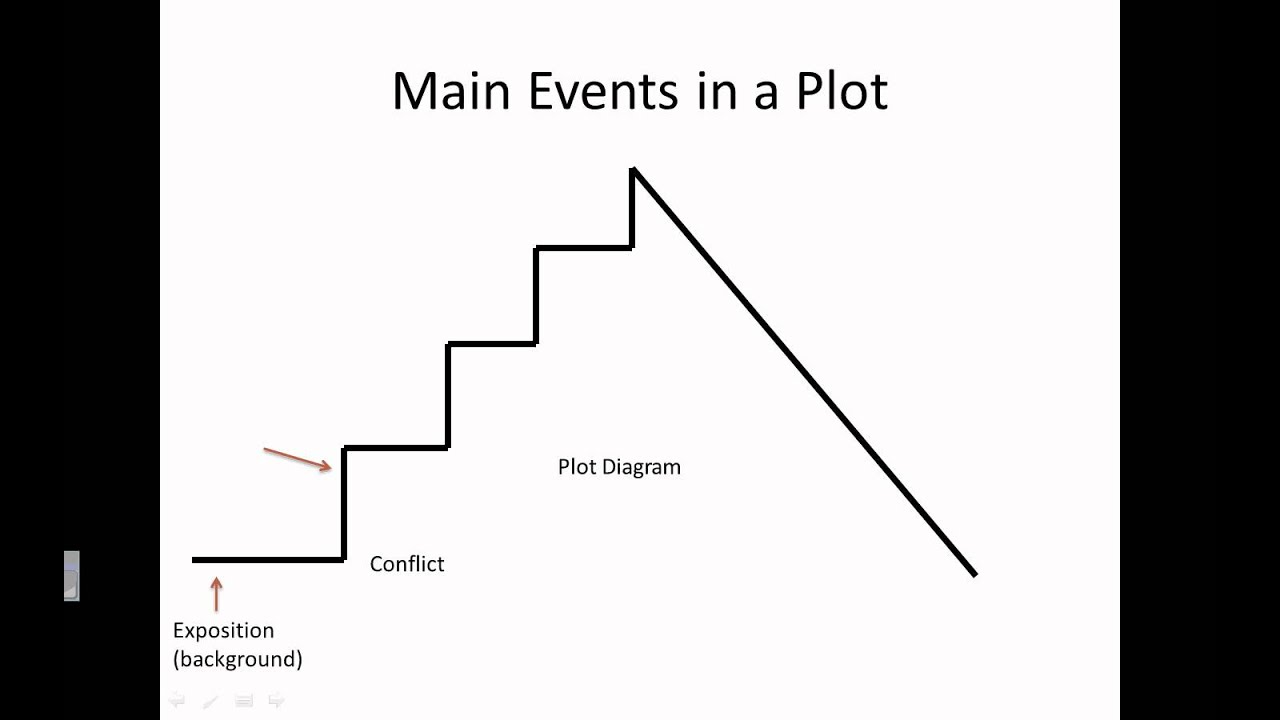

Plot the Story Structure Using a Graph. For older students, use a story graph to chart the story arc of plot sub-elements such as exposition, rising action, conflict, falling action, climax, and resolution. On the x axis, list the desired story elements chronologically. Plot the Story Structure Using a Graph For older students, use a story graph to chart the story arc of plot sub-elements such as exposition, rising action, conflict, falling action, climax, and resolution. On the x axis, list the desired story elements chronologically. Plot is the sequence of events dramatically arranged by a writer to tell a story. That is a plot structure definition in the strictest sense. Often the true genius of writing is in recognizing how to order those interrelated events.

In plot structure, exposition is the initial situation of the characters when the story begins. Short stories often begin in medias res, a Latin phrase meaning 'in the middle of things,' introducing the main conflict immediately without much backstory. For example, the exposition in Flannery O'Connor's 'A Good Man is Hard to Find' reveals that. The three act structure is perhaps the most common technique for plotting stories — widely used by screenwriters and novelists. In this post, we dissect the three acts and each of their plot points — using examples from popular culture to illustrate each point.

To create a story, a writer must first construct its central conflict, that is, its basic character goals and conflicts and the key problem of the story. Then the writer develops this central conflict into a long series of logically connected events with a beginning, middle and end; that is, with a set-up, the conflict development, and a climax. The storyline grown from a central conflict is the structure. As a simple example, consider the original Die Hard film. Its premise or central conflict is this: A tough and resourceful New York City policeman flies to Los Angeles for Christmas to win back his estranged wife, but just as he meets her, she and her co-workers are kidnapped by terrorists and held hostage in their locked down skyscraper. The policeman must evade the terrorists hunting him to rescue his wife and the other hostages, alone. The plot of Die Hard is the events that are developed from this central conflict. That is, all the murders, fights, escapes, counterattacks and relationships in the film, all the escalating complications, are applications or expansions of this central conflict. A central conflict is the plot seed that logically determines the nature of the plot tree.* The plot itself, this series of logically connected complications, is the structure. Where you place an inciting incident, plot points, act breaks and how you use sequences, the external frame or shape of a story, is only the form of your script. To emphasize the point: the structure is your series of connected events logically grown from and determined by a central conflict. Think: form is the exterior shape of your story, structure is its interior content/events. (This analysis leaves out how a writer can (and should) also organize his plot using important dramatic techniques such as mystery and suspense lines, dramatic irony, surprise and deception.)

When creating a story, content must be king: plot structure comes before form. That is, a writer (generally) creates the main character conflicts and the logically developed and connected plot events before he solidifies these into sequences and acts. Consider the issue this way: What is more important to a good story: intriguing characters and exciting conflicts organized in a dramatic, logical series of events? Or ordinary characters and clichéd events perfectly organized into sequences and acts? Also ask yourself: do you want your draft to be perfectly shaped gold or mud? I firmly believe that it is best to create the major content/events first, and then worry about how to best shape these. (That is not to say that a writer can’t go back and forth between content and form but content must come first creatively.)

And please note that I am not saying that form is not important. It is. But today there is way too much discussion of how to properly shape a story (plot points, blah blah) and not enough on how to create original characters and dramatic plots. There are many current movies that are well “structured” (plot points in the perfect places!) but the content of these films is awful.

The two hardest parts of writing a good story are creating an original, layered and integrated central conflict and then developing this into an exciting series of escalating, logically connected and climaxed events. I believe that a writer should at first focus on these two very difficult fundamentals. Let me help you construct a central conflict so that it is a rich seed that you can develop into a great plot structure.

Article originally posted here: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/write-great-script-focus-plot-structure-form-scott?trk=portfolio_article-card_title

By Glen C. Strathy

Continuing our discussion of The Seven Basic Plots by Christopher Booker, this page presents a brief outline of the plots themselves. (For more detailed discussion and examples, you should probably read the book.)

In the previous article, we noted that Booker actually discusses nine archetypal plots, but only really approves of the first seven. We're going to look at all of them here briefly, partly because we think they have all been successful and partly because its good for writers to be familiar with all of them.

Also, we noted that, although Booker argues that the basic plots all follow a five-stage structure, it is easier to reconcile his theories with those of others by presenting them in terms of a four-act structure, with the terminals of each act marked by an event called a driver or turning point. Of the five drivers found in a four-act structure, Booker only pays attention to two of them: The Call (which is either the first or second driver) and the Final Driver (which Booker gives various names to, depending on the archetypal plot. We'll omit the others too, for simplicity's sake.

So, without further ado, here are the nine basic plots...

1. Overcoming the Monster

Overcoming the Monster stories involve a hero whomust destroy a monster (or villain) that is threatening thecommunity. Usually the decisive fight occurs in the monster's lair,and usually the hero has some magic weapon at his disposal. Sometimesthe monster is guarding a treasure or holding a Princess captive,which the hero escapes with in the end.

Examples: James Bond films, The Magnificent Seven, The Day of the Triffids,

2. Rags to Riches

The Rags to Riches plot involves a hero who seemsquite commonplace, poor, downtrodden, and miserable but has thepotential for greatness. The story shows how he manages to fulfillhis potential and become someone of wealth, importance, success andhappiness.

Examples: King Arthur, Cinderella, Aladdin.

As with many of the basic plots, there are variations on Rags to Riches that are less upbeat.

Variation 1: Failure

What Booker calls the “dark” version of this story is when the hero fails to win in the end, usually because he sought wealth and status for selfish reasons. Dramatica (and most other theorists) would call this a tragedy.

Variation 2: Hollow Victory

Booker's second variation are stories where the hero “may actually achieve [his] goals, but only in a way which is hollow and brings frustration, because he again has sought them only in an outward and egocentric fashion.” Another way to describe this would be a comi-tragic ending or personal failure. In Dramatica terms, it's an outcome of success, but a judgment of failure since the hero fails to satisfactorily resolve his inner conflict.

3. Quest

Quest stories involve a hero who embarks on a journey to obtain a great prize that is located far away.

E.g. Odyssey, Watership Down, Lord of the Rings (though here the goal is losing rather than gaining the treasure), Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

Other variations on this basic plot include stories where the object being sought does not bring happiness. For example, Moby Dick, Raiders of the Lost Ark.

4. Voyage and Return

Voyage and Return stories feature a hero who journeysto a strange world that at first seems strange but enchanting.Eventually, the hero comes to feel threatened and trapped in thisworld and must he must make a thrilling escape back to the safety ofhis home world. In some cases, the hero learns and grows as a resultof his adventure (Dramatica would call this a judgment of good). Inothers he does not, and consequently leaves behind in the other worldhis true love, or other opportunity for happiness. (Dramatica wouldcall this a judgment of bad)

Examples include: The Wizard of Oz, Coraline, Robinson Crusoe, Gulliver's Travels, Lord of the Flies.

5. Comedy

Here's where things get confusing.

Traditionally, comedy has been defined in several ways.

- As any story that ends happily. In Dramatica terms this means that the story goal is obtained (outcome=success) and the main character has satisfactorily resolved his inner conflict (judgment=good).

- As a story which is humourous or satirical.

- With New Comedy or Romantic Comedy: as a drama about finding true love (usually young love). Traditionally these stories have ended in marriage.

Booker makes a valiant attempt at a better definition of comedy, but finds he cannot apply the same plot structure to it as with the other basic plots. Instead, he loosely defines Comedy in terms of three stages:

- The story takes place in a community where the relationships between people (and by implication true love and understanding) are under the shadow of confusion, uncertainty, and frustration. Sometimes this is caused by an oppressive or self-centred person, sometimes by the hero acting in such a way, or sometimes through no one's fault.

- The confusion worsens until it reaches a crisis.

- The truth comes out, perceptions are changed, and the relationships are healed in love and understanding (and typically marriage for the hero).

6. Tragedy

Tragedy, along with Comedy, is usually defined by its ending, which makes these two unlike the other basic plots. In Dramatica terms, a tragedy is a story in which the Story Goal is not achieved (outcome=failure) and the hero does not resolve his inner conflict happily (judgement=bad).

Booker's description of this plot is close to that of the classic tragedies (Greek, Roman, or Shakespearean).

Examples: Macbeth, Othello, Dr. Faustus

7. Rebirth

Rebirth stories show a hero (often a heroine) who is trapped in a living death by a dark power or villain until she is freed by another character's loving act. As with Comedy, Booker's outline of this plot is sketchy.

One of the big problems with this plot is that the hero does not solve his own problem but must be rescued by someone else, and therefore can avoid resolving his inner conflict. This is why many women hate fairy tales: the heroines are so passive.

The Disney version of Beauty and the Beast solves the problem by making Belle the main character (she rescues Beast). Though Marley intervenes to rescue Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, Scrooge ultimately chooses to change and therefore saves himself. (Hint: any new version of Sleeping Beauty should make the Prince the main character.)

Examples include Sleeping Beauty, A Christmas Carol, Beauty and the Beast, The Secret Garden

Basic Plots Booker Dislikes...

The Plot Structure Of Hamlet

The last two basic plots are ones which Booker clearly sees as inferior, because they are less about the main character embracing his feminine side.

8. Mystery

Plot Structure Pdf

First, he defines Mystery as a story in which an outsider to some horrendous event or drama (such as a murder) tries to discover the truth of what happened. Often what is being investigated in a Mystery is a story based on one of the other plots.

Booker dislikes Mysteries because the detective or investigator has no personal connection to the characters he's interviewing or the crime he's investigating. Therefore, Booker argues, the detective has no inner conflict to resolve.

This may be true many of Mysteries, including some by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle or Agatha Christie. However, in other Mystery stories the detective does have a personal stake in the plot, which gives rise to inner conflict – often a moral dilemma. Chinatown, is one example that springs to mind. So is Murder on the Orient Express and The Maltese Falcon (just to name some classics).

Nonetheless, it is true that Mysteries often do not leave one with the sense that the world has been totally healed (after all, innocent victims are still dead). This sets it apart from most of the basic stories - with the exception perhaps of Tragedy.

9. Rebellion Against 'The One'

The last of Booker's basic plots, Rebellion Against 'The One' concerns a hero who rebels against the all-powerful entity that controls the world until he is forced to surrender to that power.

The hero is a solitary figure who initially feels the One is at fault and that he must preserve his independence or refusal to submit. Eventually, he is faced with the One's awesome power and submits, becoming part of the rest of the world again.

In some versions, the One is portrayed as benevolent, as in the story of Job, while in others the reader is left convinced it is malevolent, as in 1984 or Brazil. These darker versions seem to be what make Booker less than keen on this basic plot.

Though Booker doesn't mention it, a common variation is to have the hero refuse to submit and essentially win against the power of the One. In The Prisoner, the hero eventually earns the right to discover that the One is a twisted version of himself, after which he is set free. In The Matrix, Neo's resistance eventually leads to a better world. Another example is The Hunger Games series, where Katniss's continued rebellion eventually leads to the downfall of both the original tyrant and his potential successor, resulting in a freer world.

See the previous article for more discussion of Booker's The Seven Basic Plots.

- › ›